A common question arises: is CPU overclocking still relevant, and is it advisable? CPU overclocking, which involves manually adjusting voltages to achieve frequencies higher than a processor’s default settings, has been a practice almost since the inception of personal computers. Historically, expertise in this area was a significant value proposition for many PC builders, as it offered what was perceived as “free power.”

However, the current recommendation for CPU overclocking is generally no.

Risks Associated with CPU Overclocking

Overclocking any CPU carries inherent risks. Supplying additional voltage to a processor results in faster clock speeds, but it also generates more heat. If this heat is not adequately managed by CPU coolers, radiators, and fans, it can accumulate over time, potentially leading to system crashes and instability.

Even the fastest PC becomes ineffective if it cannot maintain stability at those speeds.

Instability can manifest as immediate issues like freezes and random shutdowns, or as long-term problems, including the degradation of the silicon itself, which shortens the lifespan of the PC. Even when thermal management appears sufficient initially, issues can develop later.

Essentially, without precise knowledge and careful execution, there is a risk of damaging valuable PC components.

Diminished Overclocking Reward

While many of these risks were present during overclocking’s peak, the reward aspect has significantly changed. Previously, CPU architectures often had substantial headroom for overclocking. Processors, once manufactured, might be qualified at around 60% of their full potential, leaving up to 40% attainable through overclocking. This was a standard practice at the time.

However, as architectures evolved from single/dual-core processors to designs with 8, 16, or more cores, and as more transistors were integrated onto a single die, this headroom began to shrink. Coupled with Intel and AMD increasing the base Thermal Design Power (TDP) of their processors to deliver higher stock performance in a competitive market, modern processors now typically offer only 5% to perhaps 8% of overclocking headroom. For the vast majority of users, this minimal reward no longer justifies the aforementioned risks.

Modern CPU Architecture and Auto-Overclocking

Another reason contemporary multi-core processors are less suited for significant manual overclocks is their built-in auto-overclocking capabilities. Features like Intel’s “Turbo” speeds and AMD’s “Boost” speeds are essentially automatically enabled overclocks that processors initiate by default. When an intensive task demands extra frequency, the CPU will draw slightly more voltage to ramp up, boosting at least one core to its maximum Boost/Turbo speed. Once the task is completed, the processor scales back down to stock speeds to conserve energy and mitigate thermal risks.

A manual overclock overrides this functionality, forcing one or multiple cores to operate at an accelerated clock speed (or slightly higher) continuously. This approach reduces efficiency while offering only marginal improvements in most benchmarks.

Current CPU Performance Levels

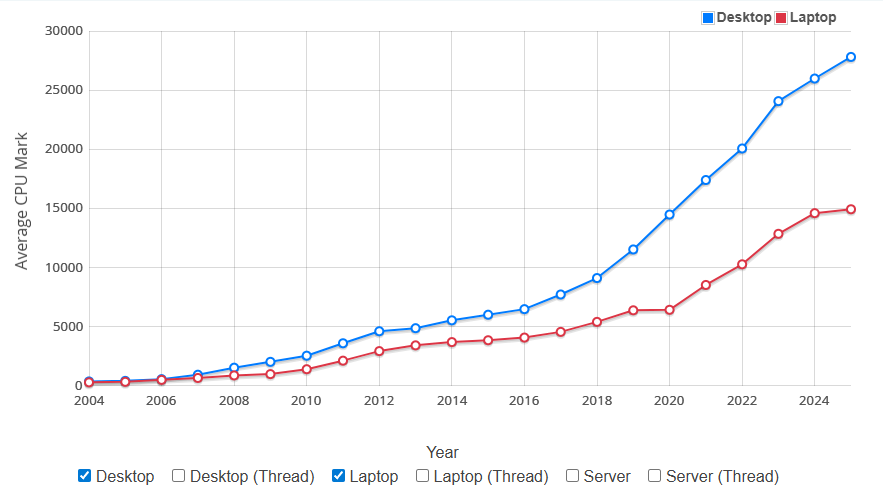

The final reason manual overclocking is rarely recommended is straightforward: current processors are exceptionally fast.  Courtesy of PassMark

Courtesy of PassMark

With some exceptions, processor speed has outpaced software development. While certain tasks like machine learning still benefit from maximum CPU performance, this is not the case for the vast majority of users. Consequently, most users are not fully utilizing their current stock CPU power, making additional performance gains from overclocking largely unnecessary, especially given the unfavorable risk/reward ratio.

Conclusion

Therefore, in 2026, CPU overclocking is not recommended for the vast majority of users. For those seeking the fastest possible PC for gaming, CAD, content creation, or AI, exploring finely crafted custom desktops is a viable option.